Reading Notes

1-3 Minute Read | Laptop or Tablet Recommended

Topics and Themes

Pareto's Principle and it's application in creativity; Overcoming perfectionism; Quantity vs. quality in sharing

Affiliate Note

When you make a purchase through links found on this site, we may earn commissions from Amazon, Perfect Circuit, and other retailers.

I let go of perfectionism long ago. It was easy. All I had to do was apply Pareto’s Principle to my creative output.

What is Pareto’s Principle?

Also known as the 80/20 rule, Pareto's Principle states that roughly 80% of effects come from 20% of causes. This means that a small number of inputs often lead to the majority of results.

Pareto’s Principle is most often applied in business, economics, and time management. Tim Ferriss popularized it in the Four-Hour Work Week.

I applied Pareto’s Principle to my creative output. It destroyed perfectionism, forever. Here’s how:

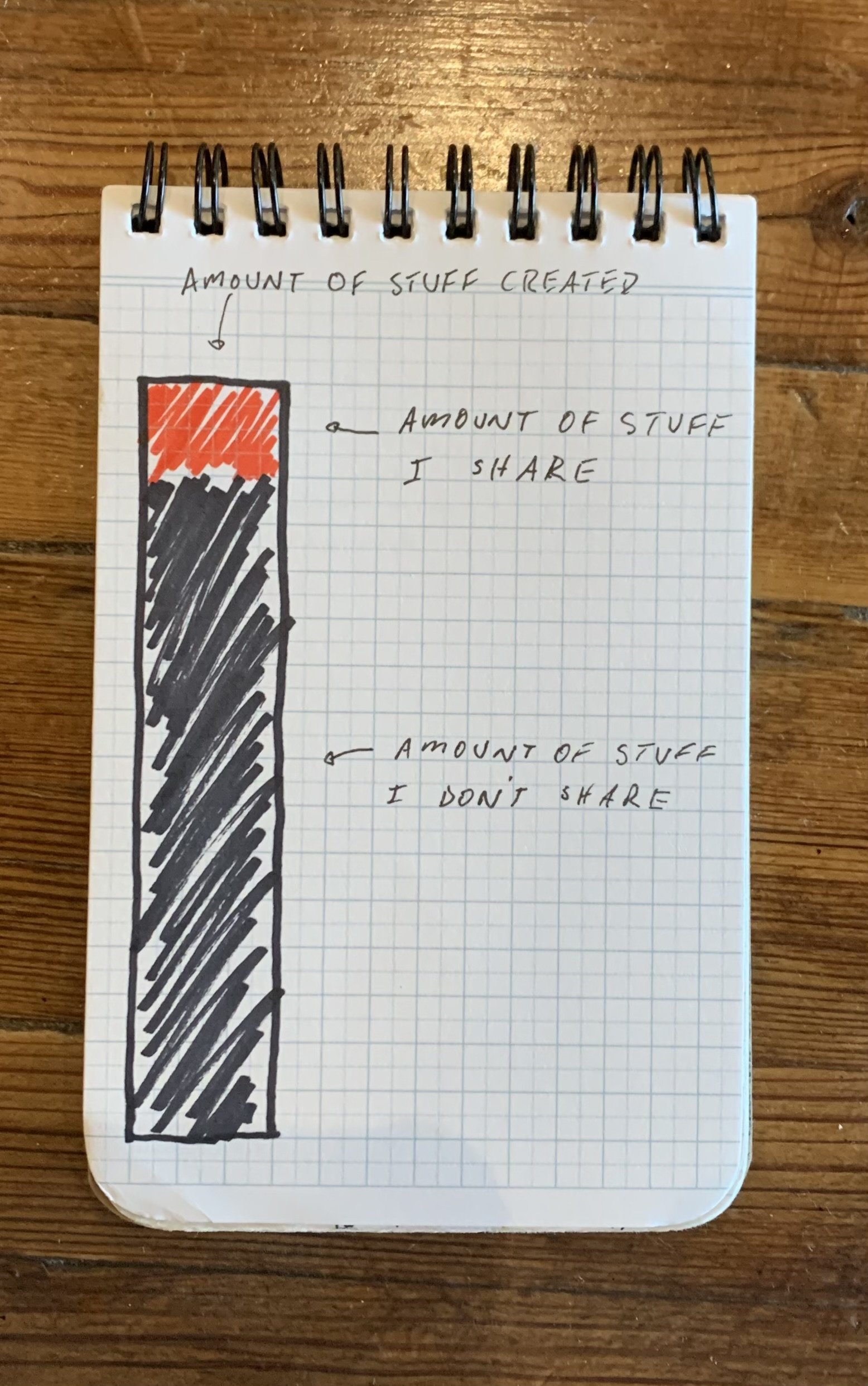

First, I increased the amount of stuff I created, aka the “inputs.” (in red and black). This includes blogs, writing, eurorack patches, orchestrations, musical sketches, and songs. I have no filter, here. I just create. Quantity over quality, as Julia Cameron states in the Artist’s Way.

Second I shared only a small amount of the “results” (in red, only). This consists of the music and blogs I release that are publicly available.

In other words, anywhere from 1% to 10% of what I create will actually get shared:

The more I write, compose, and create, the higher the number of things I will actually share.

Here’s a a cozy little one-liner that encapsulates my attitude:

The more I create, the more I’ll share.

Adapting Pareto’s Principle to your creative output can reshape your expectations in several interesting ways:

You need not share everything, since most of it won’t be shareable. This encourages you to create prolifically, knowing that most of your work will remain private and in your grasp.

Only the pieces that are worthy of polish, the ones that feel incredible and noteworthy, will actually get shared.

Of the things you share, your audience can be as vast as the entire world or as small as a single close friend. You need not share them with everyone.

So, create prolifically, share your output wisely, and say goodbye to perfectionism forever. Because perfectionism is boring as fuck.