The Perspective of the Universe

Our universe is huge.

Okay, that’s an understatement. It’s ridiculously large.

Ummmm, still an understatement. How about this: Our universe is an absolute gargantuan behemoth.

Nope. Still, an understatement. Seriously.

To get a sense of the size of the universe, let me start with how large the Earth is. If we ran a tape measure all around the earth at the equator, we’d have about 7,926 miles. That’s one long tape measure.

Now, let’s talk about the distance between the sun and the earth: 92.96 million miles. This distance is called an Astronomical Unit or AU for short. To make that distance relatable, it would take us 3,333 years to travel the length of one AU if we got in a car and set the cruise control at 80 miles per hour.

Okay, cool. Size of the Earth? Got it. Distance from sun to Earth? Yup, pretty long. What about the size of our solar system?

We can guesstimate that the size of our solar system, aka the distance from the sun to the Oort Cloud which is the furthest reaching mass currently orbiting the sun, is somewhere around 100,000 astronomical units. How many miles is that? 92.96 million times 100,000. Get out the pocket pen protector and the solar powered calculator, or just trust me that it’s a long distance.

Now, let’s talk about the size of our own Milky Way galaxy. In astronomical units, the Milky Way has a girth of somewhere in the ballpark of 6,320,400,000 AU’s. To make that number relatable, it might be easier to frame it in terms of the speed of light. If a single particle of light traveling at 670,616,629 miles per hour wished to travel from one side of the Milky Way to the other, it would take it a cool 100,000 years. Yup. Way bigger.

Let’s kick this up a notch, a big notch:

It was recently estimated that there are 2 trillion galaxies in the universe. 2,000,000,000,000 galaxies. All of varying size. Some small. Some so massive that many multiples of our fair Milky Way galaxy could fit in them. And to top that, galaxies aren’t exactly right next to each other. There’s space out there, man.

Let’s go crazy, now: We have an estimated two trillion galaxies in our universe, all of varying size. There’s room enough for all of them without them being right up in each other’s business. So, how long would it take a single particle of light to travel through each of the two trillion galaxies in succession?

And, so… um…. our universe is not just big:

It’s an embarrassment of abundance.

Now that you have a sense for how large our universe actually is, I can’t help but wonder if you are looking at your life with a bit more perspective. Perhaps you’re contemplating why you put up with your annoyingly outspoken uncle on Facebook?

It’s my firm belief that seriously pondering the size of the universe forces us to look closely at the things in our lives that no longer serve us.

When I was writing the first part of this article, I looked at the room I was sitting in and thought, “Damn, this feels tiny.” It had me scratching my head at the parts of my life that I consider small and petty, and it made me wonder why I even tolerate them. It made me want to change, and that’s the best reason to think about the size and the scale of the universe.

I believe it’s a common truth that we all want to grow and become more of ourselves throughout our lives. We want to become better people, and to do that requires embracing change. Sometimes that change needs to be radically large, and sometimes it needs to be incredibly small. But more often than not, change is most effortlessly made by deeply considering a new perspective.

After all, new perspectives have the effect of shocking and teasing us to think differently. Then, we can jump directly into the flow of change with less friction.

Perspectives Enlarge and Invigorate Us

The act of considering a different perspective expands us. It makes us think outside of ourselves, outside of our normal day-to-day problems. Busywork suddenly becomes less compelling when we have a larger perspective.

Considering the limited amount of time we have on this Earth, we ought to be incredibly careful with the way we live. The narratives we wrap ourselves in can consume us to the point where we don’t even imagine there’s a different way to live. That’s the moment when getting a fresh perspective has the potential to change everything. What was once stuck now becomes dislodged.

New perspectives jolt us in a great way. They push us outside of our comfort zones. They make us consider what we are doing on a daily basis. They give us a chance to grow larger, to expand, to become wiser. They force us to question who we are and what we are doing with the very limited amount of time we have. They offer us the chance to reveal the stories we tell ourselves.

Fresh perspectives help us become (surprise, surprise) better people.

Mark Twain knew the importance of gaining different perspectives. He thought it made a better, more decent human being. A traveler the world over, he wrote:

Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.

We are never done learning about ourselves, unless we are dead of course. To spend a life insulating ones self from any sort of change is a tragedy. By staying right in our comfort zone, by never venturing outside of what is easy and simple, we can’t possibly learn whether we are living inline with our core values.

And it’s a terrible thing to live our lives in a way that makes us feel extremely unhappy.

The Fear of Living The Wrong Story

Does it frighten you to think that you might be living a life that doesn’t really work for you?

It frightens me sometimes.

We could be living our lives in a way that is completely disingenuous to our values. We might be ignoring what we really care about.

You might care about your family, but the life that you’re living might lead you to treat them very badly. You might care about gaining wealth, but the story you’re living might lead you to spending more money than you’re saving. You might care about the environment, but the story you’re living might lead you to not giving your support to organizations that could do good work on your behalf. It’s important for our stories to reflect our values.

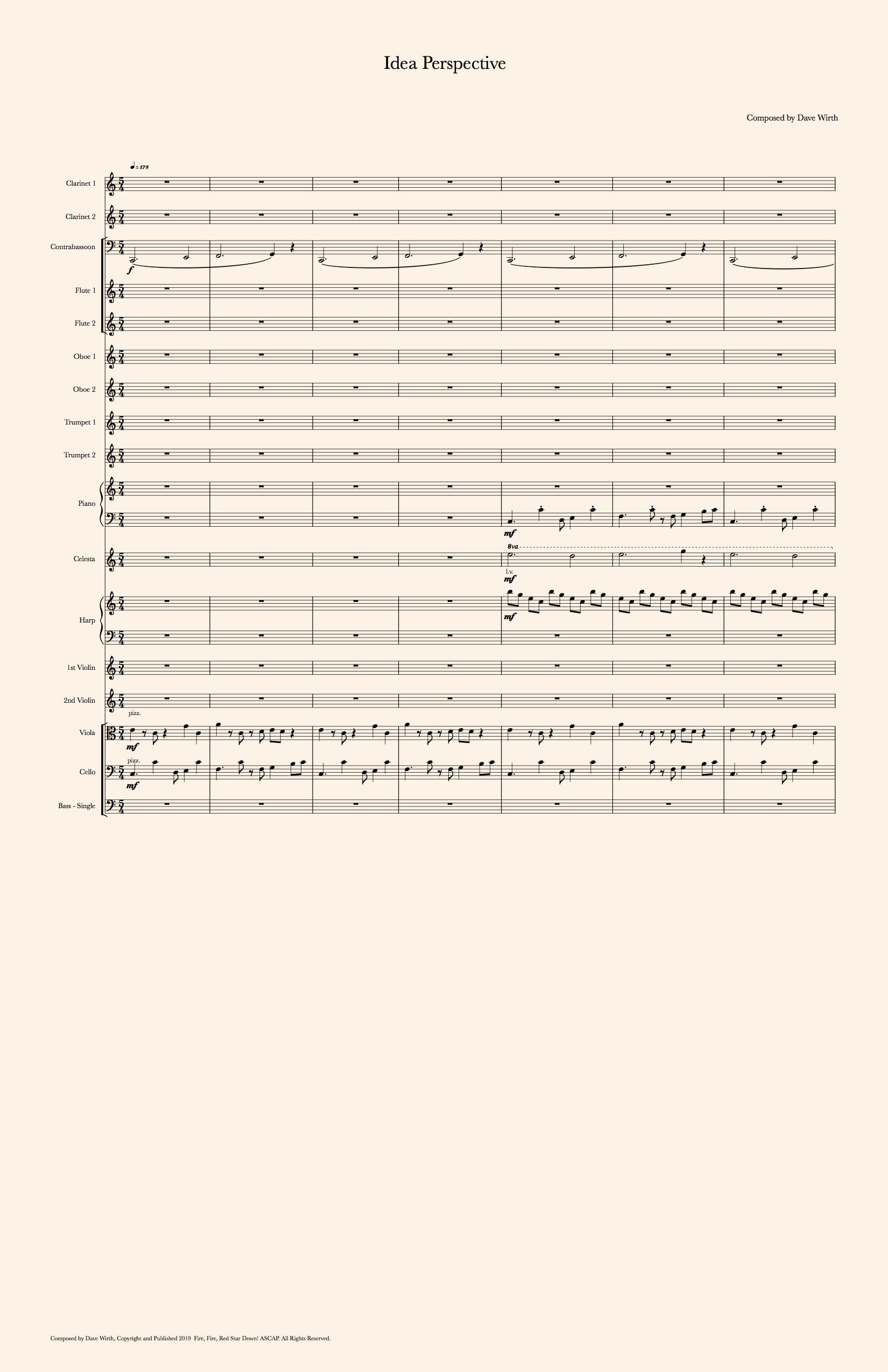

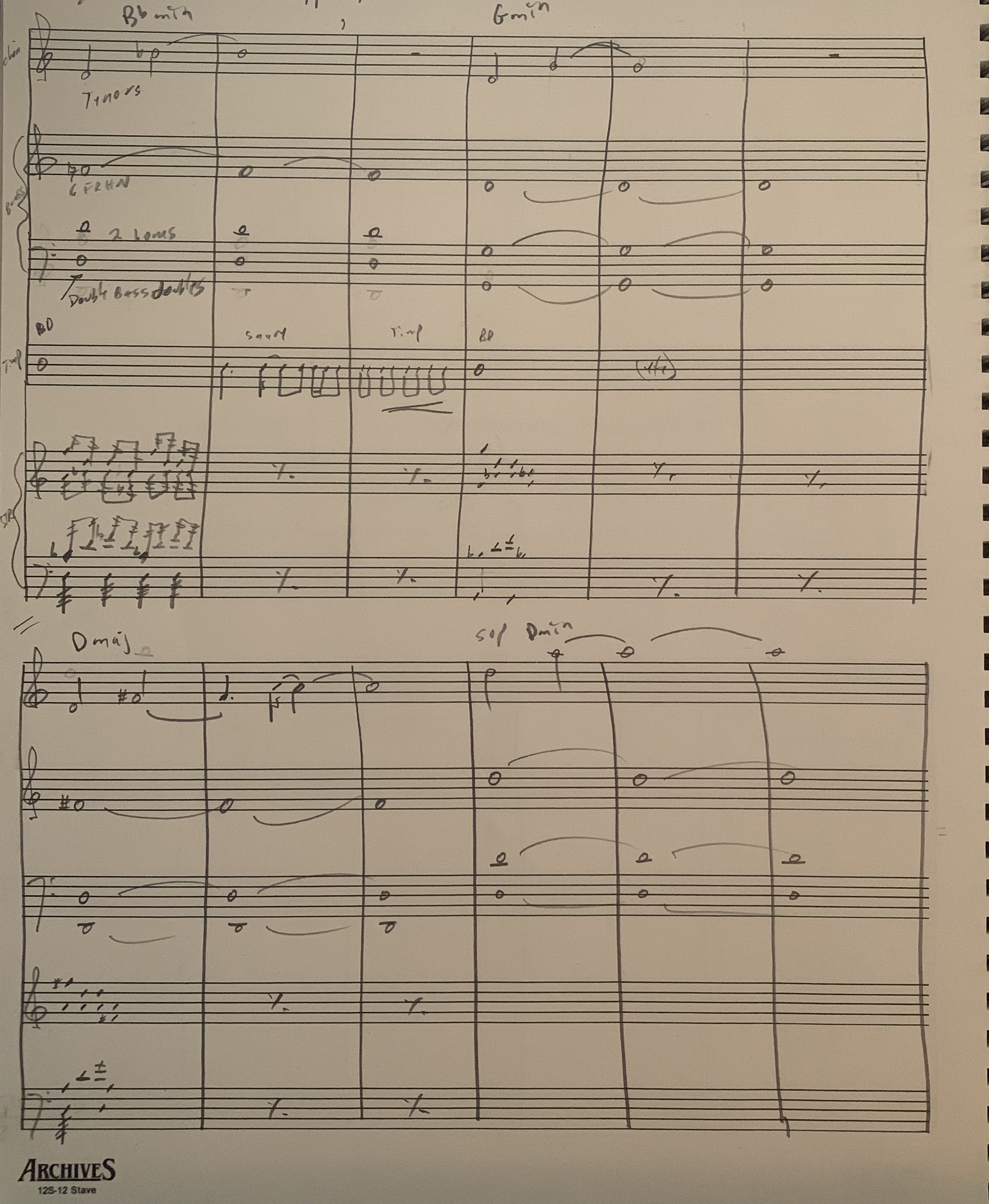

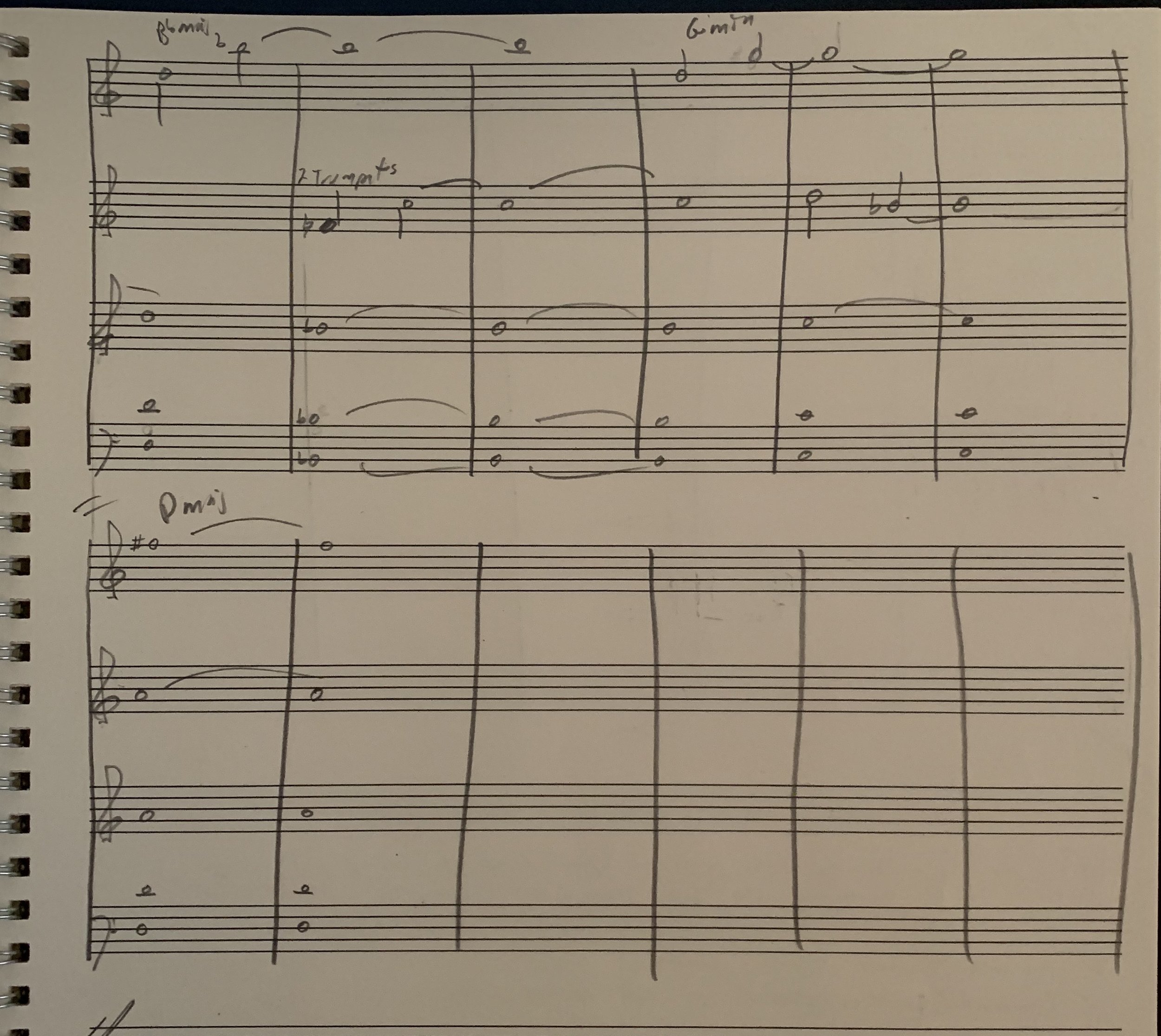

I value both music and creativity. My story is that I must compose music. If I don’t compose, I am being disingenuous to my values. If I don’t sit down and improvise at the piano, if I don’t experiment with a synthsizer, if I don’t work on composing with an orchestra, my entire being revolts. I need to compose music, and I need to do it often. I feel better after doing it. Therefore, my story (I must compose music) is inline with my values (music and creativity).

It’s important to reveal how we might not be living in a way that is harmonious with our inner values. The stories we live, i.e. the statements we tell ourselves either consciously or subconsciously, are important to both reveal and take stock of. If we are living the wrong stories, we are wasting the precious time we have on this Earth.

Quite possibly the greatest way to reveal whether or not the stories that we tell ourselves are inline with our values is to experience a radically different perspective. Something totally outside and strange, something otherworldly. Something that really smacks us in the head and makes us ponder what we’re doing with our time.

Perspectives Come In All Sizes

The shock of experiencing a new perspective forces us to evaluate the stories we tell ourselves. It doesn’t have to be completely overwhelming and dramatic, by the way. It certainly could be epic, but sometimes the perspective that delivers the shock can be incredibly intimate and subtle. It could be small, barely perceptible, almost without weight.

The perspective of the size of the universe can shock you right out of the silly things you put up with in your life, including your uncle’s questionable Facebook posts. Given enough attention however, fully experiencing a small scale perspective can almost do the opposite: It has the potential to reveal a detail about living that might have eluded you. One of my favorite small-scale perspectives to think about is just how amazing it is that a caterpillar can change into a butterfly.

Think about it: What starts as a squirmy little worm ends up as a magnificent living thing, resplendent with wings of colorful detail. How does it get there? What happens to it inside the cocoon? We may understand what it’s going through to become a butterfly, but can we truly know?

Maybe, maybe not.

Imagine if we put away our to-do lists and looked closely at the transformation. What if you truly committed to observing it, start to finish? Sure, it would take some time. Sometimes it would be incredibly boring, of course. But when the butterfly emerges, it will feel magical. It will feel like a miracle. It will feel like the most impressive thing you’ve witnessed all year.

The perspective of the butterfly transformation, as small as it is, can change us just as deeply as contemplating the large-scale perspective of the size of the universe. When we experience a perspective that has a large scale, we tend to take a look the things we do daily and question if they are important. Conversely, when we experience a small-scale perspective, we may be granted access to an expertly hidden detail about our lives. In either case, something hidden becomes known.

My point is this: Perspective can come in any size, but a fresh perspective changes us nonetheless.

Music Provides Fresh Perspectives, Too.

Have you ever been completely arrested by a song? Have you listened to a piece of music that put you in a trance? Did you wonder where the time went, after the piece was finished?

Of course you have!

Music is important. We all have desert island records because we can’t live without music. It’s something that speaks to our deepest selves.

When we listen to music that captures our attention, it also makes us look closely at who we really are, how we are acting. Music’s strength is in offering that fresh perspective without it feeling like it’s an imposition. I experienced this when I first heard Sigur Ros’s (), probably my favorite record of all-time. The discovery of this album changed my life and altered the narrative I told myself. It provided a perspective that I didn’t even know that I needed. Here’s the story:

When I was studying classical music in Rochester NY in the early 2000’s, I took a road trip to Washington DC to hang out with some friends. I remember that we all visited a record shop. The Sigur Ross album () was set up in a listening booth, close to the front window of the store. It was winter, but the sun was warming the city. I was seduced by the warmth of the window. I took off my hat. I put on the headphones.

Within one minute, I was completely transported. I had never heard anything so beautiful in my life. I had never heard something so slow that had so much energy and beauty and hope to it.

Within five minutes, my life was forever changed.

Where before I was only interested in becoming the best classical guitarist possible, I now no longer cared. The music of Sigur Ros’s () showed me that I was living the wrong story. It showed me that I need to value my creativity. It made me focus deeper on composing and writing music.

The discovery of that album changed my perspective and altered the course of my life. That’s the power of a compelling new perspective.

Music is a Language to Communicate Perspective

Music can effortlessly communicate a different perspective to the audience, and it does so in a way that goes right to our emotional core. It can change people just like Sigur Ros’s () changed me.

When the music captures the perspective that a film seeks to communicate, the result is magical. It doesn’t matter if the music sounds large, like Hans Zimmer’s score for Dunkirk, or small, like Nicholas Britell’s score for Moonlight. When the music is appropriately matched to the perspective that the film seeks to communicate, the result is powerful because the perspective is 100% compelling.

And to spell it out: The more compelling and fresh a perspective in a movie, the wider the reach and the more successful that movie will be.

I think it behooves those in the entertainment business to be extremely careful with music in a film because it has the best chance to communicate perspective to the audience in a non-invasive way. This is why I never want to misjudge who’s perspective is the most important in a movie that I’m working on. Doing so would cause me to write music that doesn’t match the size of the film, the scale of the production, or even the vision the director had for the film. Doing so would cause the film to be less powerful. Much of my time is figuring out who has the dominant perspective of the story. If I can figure that out, then I’ve figured out how I ought to compose the music.

I love thinking about who owns the perspective in a film. When I have that knocked, so many other issues in a film score become clear. For example, the size and scale of a film score can be revealed by understanding who the story belongs to.

I want to talk about who the story belongs to in more detail, but to get there I need to revisit a topic that you may have learned many years ago in middle school. I promise you, no embarrassing stories.

Finding The Perspective That Commands The Story

The music on your film is a powerful tool to deliver fresh perspectives, and believe me: Fresh perspectives are vital. This article goes deep into Audio Perspective, i.e. the music being written from the most compelling perspective in the story. Mastering audio perspective can make your movies far more relevant, relatable, and successful.

If you’ve ever wondered how you can use music to communicate a compelling perspective, this article is for you. Let’s hit it!