No one wants to talk about death, but when musicians play music for people in hospice, you can’t deny how awesome that is:

Wayne Miles has not got the energy to open his eyes, but a faint smile flickers across his face as he silently mouths the words to the John Denver song Some Days Are Diamonds.

The 59-year-old Glasshouse Mountains man is dying from cancer, and amid the pain and grief music provides solace.

The former truck driver's love for country music is being nurtured by music therapist Tracie Wicks.

She sits with him at his bedside, strumming a guitar or playing the keyboard, and crooning Slim Dusty and John Denver songs that fill the dedicated music room in the Dove Palliative Care wing of the Caloundra Hospital.

This orchestra helps those who are deaf to feel the vibrations of music.

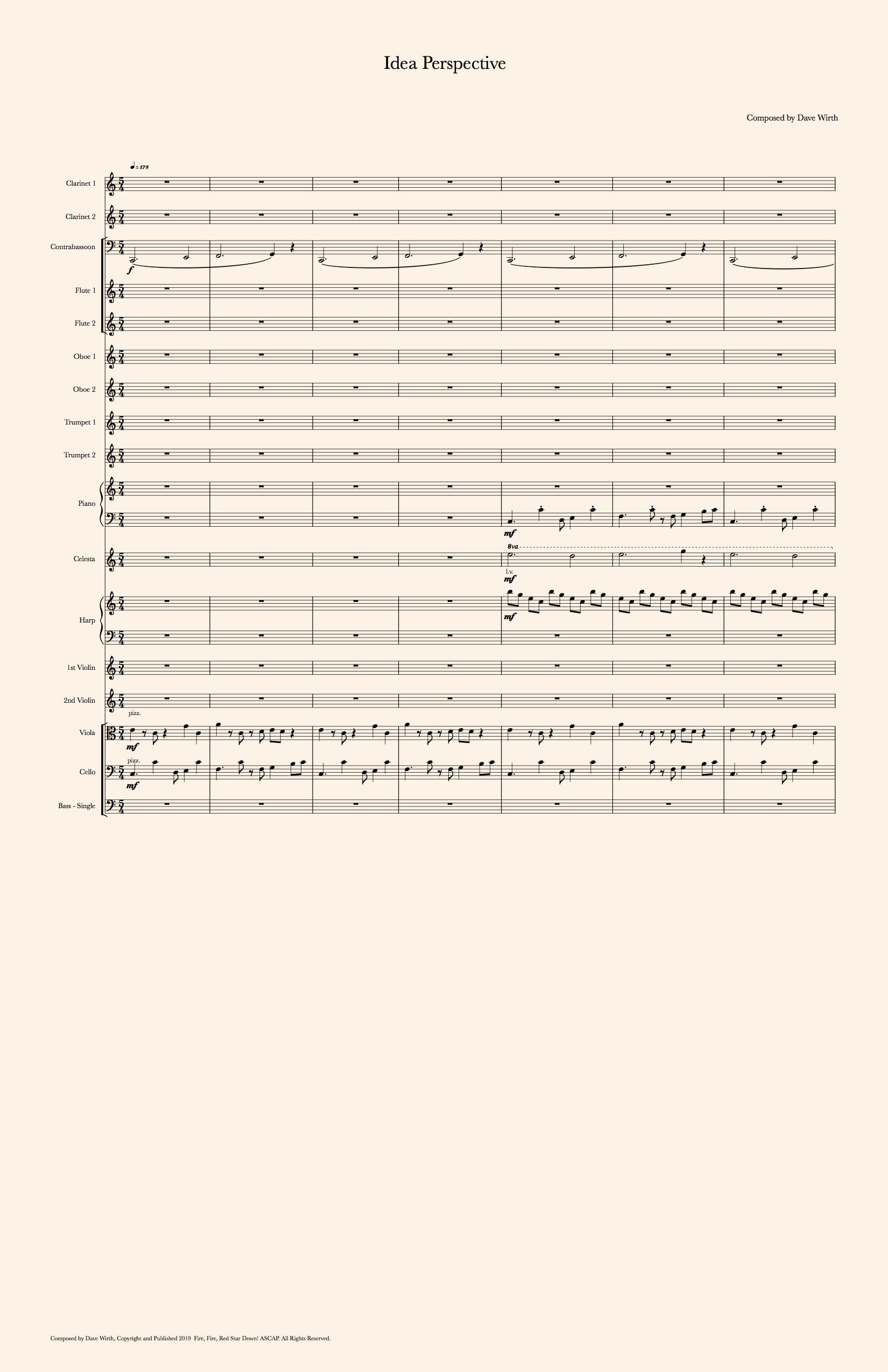

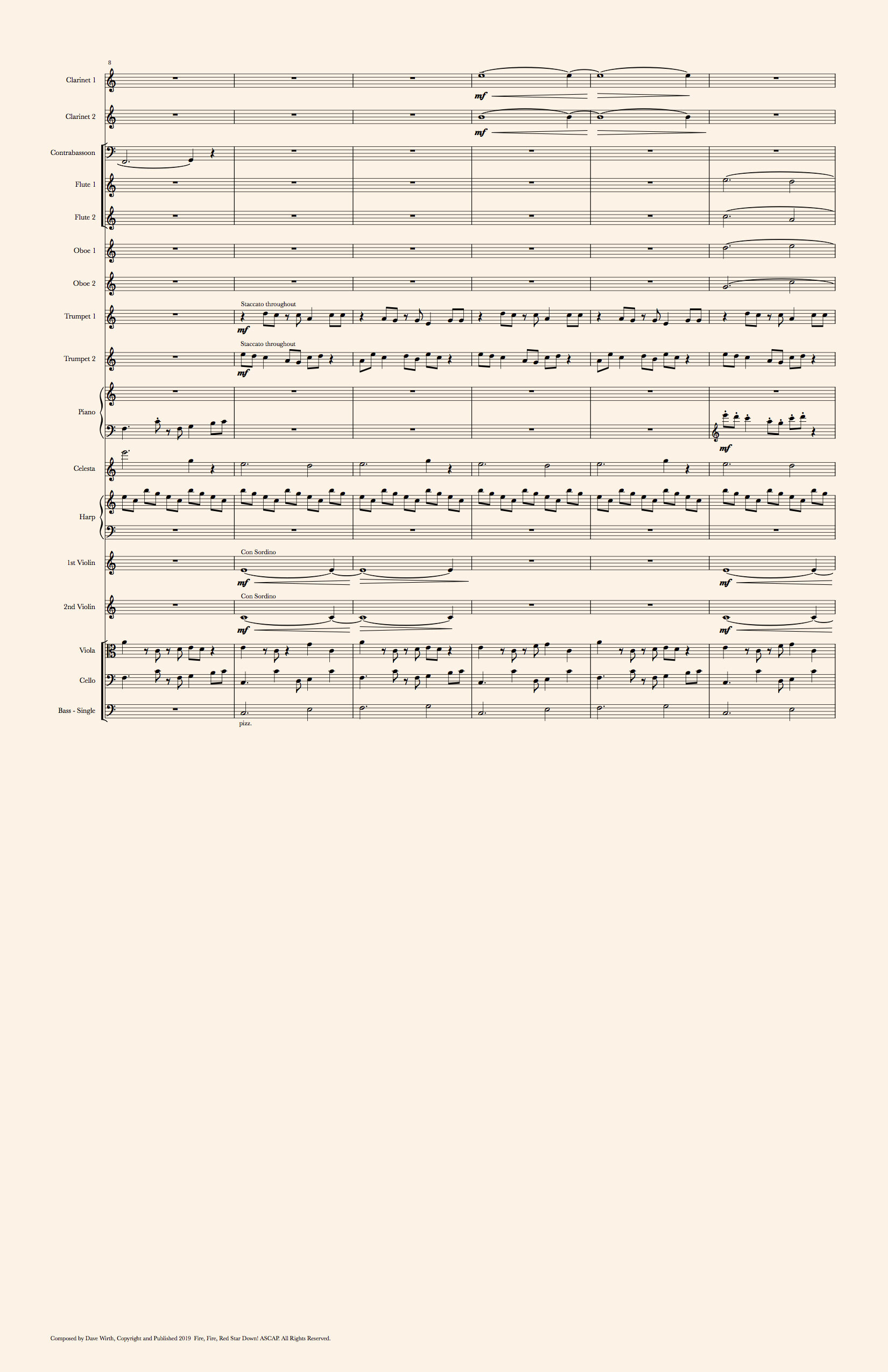

Flutes and both violins in first part, low strings and high clarinet Sfz in the second.

Modular synthesizer enthusiast with physical disability hacks his arm prosthesis to control synthesizers with his mind:

This is so awesome:

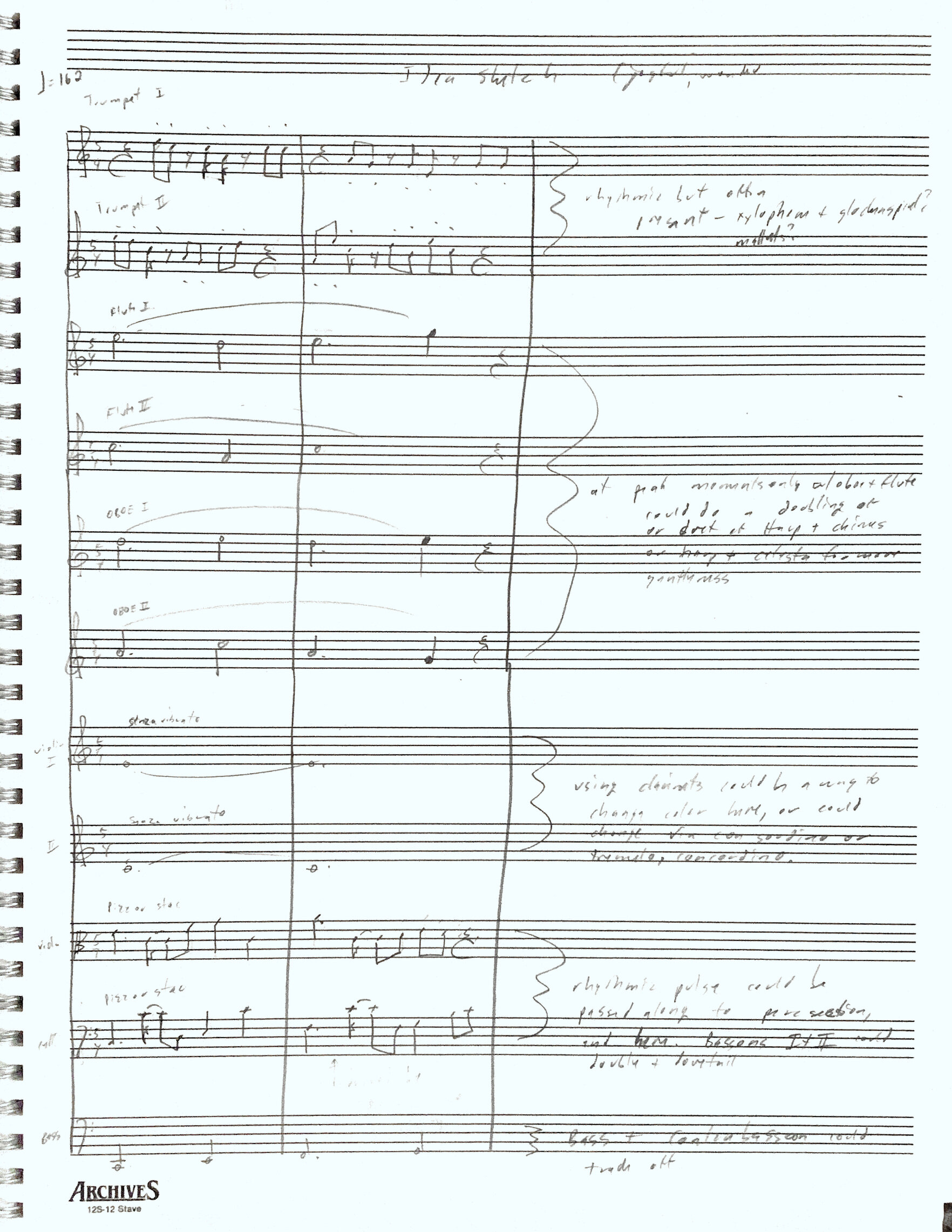

11 second cue: Joyous and triumphant. Measured string tremolos, french horns, trumpet, hard mallet timpani, triangle tremolo:

Got invited by Jonas Wikstrand to do a co-demonstration/presentation on film composing at Thinkery21 tomorrow night. Lots of production peeps will be doing demos. See you there?

24 second epic drum cue sketch: WARNING! THIS IS LOUD! Taiko drums, toms, chinese tam tam, french horn ensemble, tremolo strings:

I published an article on this blog not too long ago about emotional impact in film scoring.

To me, we composers use sample libraries to create music that sounds like an orchestra without hiring one out. This has benefits and also some intense drawbacks. In my view: Sample libraries are great tools if we use them right.

From the article:

Emotional impact upon the audience of any film comes from humans who are primed and encouraged to bring their own emotions to the table, who deliver their own emotions in their performances, who take part in a story that has real impact upon the lives of the viewer.

Can this idea apply to the music of a film?

Oh my my, oh hell yes.

The technology for creating entire symphonies in a bedroom is available. It’s even cheap to produce a recording! To create a massive-sounding orchestral film score, many film composers nowadays rely upon sample libraries that include tens of thousands of individual sounds of instruments in the orchestra. The trade off is that they also have to program and then manipulate all of these samples so that they can create the score. In other words, the samples don’t come prearranged for the composer. The composer has to reprogram the sample library to sound appropriate for the film.

This small, almost insignificant detail, the fact that composers have to rearrange a sample so that it can be appropriate for a film score, has a remarkably stark effect on the emotional impact of a film.

Stay with me on this.

Before I get into why, we need to jump into a favorite subject of musicians and the online forums they frequent: Sample libraries...

Pizzicato strings, french horns, flutes, and celeste

The timpani as a melodic instrument, orchestral chimes, offstage flutes and clarinets, and senza vibrato violas. Dark and menacing!

Composed by Dave Wirth, Copyright and Published 2020 Fire, Fire, Red Star Down! ASCAP. All Rights Reserved.

Sudoku:

Gradus Ad Parnassum (counterpoint):

Reading Notes

27 Minute Read | Laptop or Tablet Recommended

Topics and Themes

Perspective in film music, Narrative and documentary filmmaking perspectives, Size and scale of film scores, Choosing the best audio perspective for a film

The Perspective of the Universe

Our universe is huge.

Okay, that’s an understatement. It’s ridiculously large.

Ummmm, still an understatement. How about this: Our universe is an absolute gargantuan behemoth.

Nope. Still, an understatement. Seriously.

To get a sense of the size of the universe, let me start with how large the Earth is. If we ran a tape measure all around the earth at the equator, we’d have about 7,926 miles. That’s one long tape measure.

Now, let’s talk about the distance between the sun and the earth: 92.96 million miles. This distance is called an Astronomical Unit or AU for short. To make that distance relatable, it would take us 3,333 years to travel the length of one AU if we got in a car and set the cruise control at 80 miles per hour.

Okay, cool. Size of the Earth? Got it. Distance from sun to Earth? Yup, pretty long. What about the size of our solar system?

We can guesstimate that the size of our solar system, aka the distance from the sun to the Oort Cloud which is the furthest reaching mass currently orbiting the sun, is somewhere around 100,000 astronomical units. How many miles is that? 92.96 million times 100,000. Get out the pocket pen protector and the solar powered calculator, or just trust me that it’s a long distance.

Now, let’s talk about the size of our own Milky Way galaxy. In astronomical units, the Milky Way has a girth of somewhere in the ballpark of 6,320,400,000 AU’s. To make that number relatable, it might be easier to frame it in terms of the speed of light. If a single particle of light traveling at 670,616,629 miles per hour wished to travel from one side of the Milky Way to the other, it would take it a cool 100,000 years. Yup. Way bigger.

Let’s kick this up a notch, a big notch:

It was recently estimated that there are 2 trillion galaxies in the universe. 2,000,000,000,000 galaxies. All of varying size. Some small. Some so massive that many multiples of our fair Milky Way galaxy could fit in them. And to top that, galaxies aren’t exactly right next to each other. There’s space out there, man.

Let’s go crazy, now: We have an estimated two trillion galaxies in our universe, all of varying size. There’s room enough for all of them without them being right up in each other’s business. So, how long would it take a single particle of light to travel through each of the two trillion galaxies in succession?

And, so… um…. our universe is not just big:

It’s an embarrassment of abundance.

Now that you have a sense for how large our universe actually is, I can’t help but wonder if you are looking at your life with a bit more perspective. Perhaps you’re contemplating why you put up with your annoyingly outspoken uncle on Facebook?

It’s my firm belief that seriously pondering the size of the universe forces us to look closely at the things in our lives that no longer serve us.

When I was writing the first part of this article, I looked at the room I was sitting in and thought, “Damn, this feels tiny.” It had me scratching my head at the parts of my life that I consider small and petty, and it made me wonder why I even tolerate them. It made me want to change, and that’s the best reason to think about the size and the scale of the universe.

I believe it’s a common truth that we all want to grow and become more of ourselves throughout our lives. We want to become better people, and to do that requires embracing change. Sometimes that change needs to be radically large, and sometimes it needs to be incredibly small. But more often than not, change is most effortlessly made by deeply considering a new perspective.

After all, new perspectives have the effect of shocking and teasing us to think differently. Then, we can jump directly into the flow of change with less friction.

Perspectives Enlarge and Invigorate Us

The act of considering a different perspective expands us. It makes us think outside of ourselves, outside of our normal day-to-day problems. Busywork suddenly becomes less compelling when we have a larger perspective.

Considering the limited amount of time we have on this Earth, we ought to be incredibly careful with the way we live. The narratives we wrap ourselves in can consume us to the point where we don’t even imagine there’s a different way to live. That’s the moment when getting a fresh perspective has the potential to change everything. What was once stuck now becomes dislodged.

New perspectives jolt us in a great way. They push us outside of our comfort zones. They make us consider what we are doing on a daily basis. They give us a chance to grow larger, to expand, to become wiser. They force us to question who we are and what we are doing with the very limited amount of time we have. They offer us the chance to reveal the stories we tell ourselves.

Fresh perspectives help us become (surprise, surprise) better people.

Mark Twain knew the importance of gaining different perspectives. He thought it made a better, more decent human being. A traveler the world over, he wrote:

Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.

We are never done learning about ourselves, unless we are dead of course. To spend a life insulating ones self from any sort of change is a tragedy. By staying right in our comfort zone, by never venturing outside of what is easy and simple, we can’t possibly learn whether we are living inline with our core values.

And it’s a terrible thing to live our lives in a way that makes us feel extremely unhappy.

The Fear of Living The Wrong Story

Does it frighten you to think that you might be living a life that doesn’t really work for you?

It frightens me sometimes.

We could be living our lives in a way that is completely disingenuous to our values. We might be ignoring what we really care about.

You might care about your family, but the life that you’re living might lead you to treat them very badly. You might care about gaining wealth, but the story you’re living might lead you to spending more money than you’re saving. You might care about the environment, but the story you’re living might lead you to not giving your support to organizations that could do good work on your behalf. It’s important for our stories to reflect our values.

I value both music and creativity. My story is that I must compose music. If I don’t compose, I am being disingenuous to my values. If I don’t sit down and improvise at the piano, if I don’t experiment with a synthsizer, if I don’t work on composing with an orchestra, my entire being revolts. I need to compose music, and I need to do it often. I feel better after doing it. Therefore, my story (I must compose music) is inline with my values (music and creativity).

It’s important to reveal how we might not be living in a way that is harmonious with our inner values. The stories we live, i.e. the statements we tell ourselves either consciously or subconsciously, are important to both reveal and take stock of. If we are living the wrong stories, we are wasting the precious time we have on this Earth.

Quite possibly the greatest way to reveal whether or not the stories that we tell ourselves are inline with our values is to experience a radically different perspective. Something totally outside and strange, something otherworldly. Something that really smacks us in the head and makes us ponder what we’re doing with our time.

Perspectives Come In All Sizes

The shock of experiencing a new perspective forces us to evaluate the stories we tell ourselves. It doesn’t have to be completely overwhelming and dramatic, by the way. It certainly could be epic, but sometimes the perspective that delivers the shock can be incredibly intimate and subtle. It could be small, barely perceptible, almost without weight.

The perspective of the size of the universe can shock you right out of the silly things you put up with in your life, including your uncle’s questionable Facebook posts. Given enough attention however, fully experiencing a small scale perspective can almost do the opposite: It has the potential to reveal a detail about living that might have eluded you. One of my favorite small-scale perspectives to think about is just how amazing it is that a caterpillar can change into a butterfly.

Think about it: What starts as a squirmy little worm ends up as a magnificent living thing, resplendent with wings of colorful detail. How does it get there? What happens to it inside the cocoon? We may understand what it’s going through to become a butterfly, but can we truly know?

Maybe, maybe not.

Imagine if we put away our to-do lists and looked closely at the transformation. What if you truly committed to observing it, start to finish? Sure, it would take some time. Sometimes it would be incredibly boring, of course. But when the butterfly emerges, it will feel magical. It will feel like a miracle. It will feel like the most impressive thing you’ve witnessed all year.

The perspective of the butterfly transformation, as small as it is, can change us just as deeply as contemplating the large-scale perspective of the size of the universe. When we experience a perspective that has a large scale, we tend to take a look the things we do daily and question if they are important. Conversely, when we experience a small-scale perspective, we may be granted access to an expertly hidden detail about our lives. In either case, something hidden becomes known.

My point is this: Perspective can come in any size, but a fresh perspective changes us nonetheless.

Music Provides Fresh Perspectives, Too.

Have you ever been completely arrested by a song? Have you listened to a piece of music that put you in a trance? Did you wonder where the time went, after the piece was finished?

Of course you have!

Music is important. We all have desert island records because we can’t live without music. It’s something that speaks to our deepest selves.

When we listen to music that captures our attention, it also makes us look closely at who we really are, how we are acting. Music’s strength is in offering that fresh perspective without it feeling like it’s an imposition. I experienced this when I first heard Sigur Ros’s (), probably my favorite record of all-time. The discovery of this album changed my life and altered the narrative I told myself. It provided a perspective that I didn’t even know that I needed. Here’s the story:

When I was studying classical music in Rochester NY in the early 2000’s, I took a road trip to Washington DC to hang out with some friends. I remember that we all visited a record shop. The Sigur Ross album () was set up in a listening booth, close to the front window of the store. It was winter, but the sun was warming the city. I was seduced by the warmth of the window. I took off my hat. I put on the headphones.

Within one minute, I was completely transported. I had never heard anything so beautiful in my life. I had never heard something so slow that had so much energy and beauty and hope to it.

Within five minutes, my life was forever changed.

Where before I was only interested in becoming the best classical guitarist possible, I now no longer cared. The music of Sigur Ros’s () showed me that I was living the wrong story. It showed me that I need to value my creativity. It made me focus deeper on composing and writing music.

The discovery of that album changed my perspective and altered the course of my life. That’s the power of a compelling new perspective.

Music is a Language to Communicate Perspective

Music can effortlessly communicate a different perspective to the audience, and it does so in a way that goes right to our emotional core. It can change people just like Sigur Ros’s () changed me.

When the music captures the perspective that a film seeks to communicate, the result is magical. It doesn’t matter if the music sounds large, like Hans Zimmer’s score for Dunkirk, or small, like Nicholas Britell’s score for Moonlight. When the music is appropriately matched to the perspective that the film seeks to communicate, the result is powerful because the perspective is 100% compelling.

And to spell it out: The more compelling and fresh a perspective in a movie, the wider the reach and the more successful that movie will be.

I think it behooves those in the entertainment business to be extremely careful with music in a film because it has the best chance to communicate perspective to the audience in a non-invasive way. This is why I never want to misjudge who’s perspective is the most important in a movie that I’m working on. Doing so would cause me to write music that doesn’t match the size of the film, the scale of the production, or even the vision the director had for the film. Doing so would cause the film to be less powerful. Much of my time is figuring out who has the dominant perspective of the story. If I can figure that out, then I’ve figured out how I ought to compose the music.

I love thinking about who owns the perspective in a film. When I have that knocked, so many other issues in a film score become clear. For example, the size and scale of a film score can be revealed by understanding who the story belongs to.

I want to talk about who the story belongs to in more detail, but to get there I need to revisit a topic that you may have learned many years ago in middle school. I promise you, no embarrassing stories.

Finding The Perspective That Commands The Story

Do you remember point of view? Here’s a refresher: Think of first, second, and third person. I’ll make this quick and quirky:

First person is the "I, we, us" point of view. A good example is this article. I have written in the first person point of view, aka mine. As a side tidbit, I’ve noticed people tend to avoid talking in the first person when they are trying to slip out of taking any responsibility.

The second person point of view is "You." This point of view is what most sports stars and business leaders talk in. If anyone has a theory as to why these two groups of people tend to speak in this point of view, please share your theory in the comments section of this article. I'm curious.

Finally, we come to the third person, which is "He, She, It." To be simplistic, you could call this the narrator's perspective. Sally did this, John did that, the furball went left, the goop of slime went right. Everyone thought it was a good idea except Cindy who was against it at the start. Etc, etc, etc.

Point of view can illustrate who the story belongs to, in a way. And the most interesting thought is that who the story belongs to is not always a single character. Sometimes, it’s not even a character at all. Sometimes, the story belongs to an idea, or to the world it takes place in. I’ll get there in a moment.

To get back to the point, and now that you are refreshed on the concept of point of view, it’s time to bring everything together and wrap a nice bow on top.

Are you ready?!? This is what I’ve used 10 minutes of your precious time to get to. It’s really important for the success of your films. Listo? Here goes:

Knowing who the story belongs to reveals the most appropriate size, scale, and tone of film score.

The idea is to find out exactly who the story belongs to and search for the size and tone of score that fits the perspective that owns the story.

A story that his owned by an incredibly large perspective ought to have music that is composed in a large way, like epic orchestral arrangements. A story that is owned by an intimate and small perspective is likely best paired with music that is composed in a more intimate manner, maybe just an acoustic guitar.

If you’re with me, if you agree that whomever owns the story owns the perspective, and that the size of that perspective dramatically affects the size and scale of the film score, then it’s time to dissect this issue with more depth. Plus, it’s time to get into some music examples. Let there be music! No more exposition!

I want to start with the very largest audio perspective possible. Without a doubt, this is the very most popular audio perspective in Hollywood.

In my analogy of size, this perspective is undoubtedly represented by how the universe can have enough room to house an estimated 2 trillion galaxies.

I call it: World Perspective.

World Perspective

I watched Blade Runner 2049 in the theater. I suspected it's deep brilliance the first time I watched it, but the second viewing solidified my opinion.

In listening intently to the soundtrack, done by the hard-working Hans Zimmer, I ruminated on how large his score for this movie was. I also pondered his other scores and how large his work tends to be in general. Zimmer can create large-sounding music scores so easily and effortlessly, and I honestly think that's what he's paid for (which is awesome!).

It gets more interesting when you start to think why this sort of largeness works for the score for Blade Runner 2049; It takes a birds-eye view of all the characters in the movie. Sure, there are moments when it gets up close and personal, but the film's story belongs to something that is all-encompassing, vast, and extremely depressing (to be honest): The world that it is set in.

In the movie, we feel that world, are affected by the world, are immersed in that world. It's still Earth, but it's in the future, and there have been changes... not all of them have been good, either.

I love how Zimmer’s score creates such a deep and visceral connection to the world these characters are inside, how it informs all of the actions of the characters, and how it gives the viewer this incredible context for the story to unfold.

This is why world perspective is so popular: The bigger the music, the better the chance of keeping the audience inside the movie, and completely engaged.

And I also want to be perfectly clear: I love world perspective scores. I think they are super fun to listen to and compose.

To me, world perspective is successful if it expands the physical reach of the big screen far beyond it's rectangular dimensions. Because music has a way of pulling us inside the film, immersing us into understanding what's happening in a film, we no longer see that screen anymore; We see and feel the world beyond it. This perspective is all about convincing the audience that they are inside the world of that story. If that means kicking, punching, overwhelming, and pulling them into that world, than so be it!

So, does world perspective scores only occur on sci-fi films? Or big epic dramas? Not at all. There are other films that are less “big” that a world perspective works on, and one of them is an absolute classic.

An excellent example of a smaller world perspective score and movie would be The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. The music isn't as physically "large" as Hans Zimmer's scores, but Ennio Morricone’s music manages to transport me instantly inside the movie. I’m pretty sure it does for you too.

My point is that we don't need to have this massively large-sounding score to nail a world perspective. The music just needs to enlarge the screen.

The World Perspective in Practice

If the point of world perspective is to enlarge the screen, to make that world so big and crazy that it pulls the viewer deep inside the movie, than it’s time to go really big. No modesty here. It’s time to go epic.

Acheiving a world perspective often, but not always, requires the loudest and most powerful orchestral and/or synthesizer arrangements. Further, the chord progressions have to feel epic. Following traditional western music harmony is not really an option here. It was time to go big and bright, huge Hollywood orchestra style!

In this example of world perspective, I ended up choosing to do a sci-fi theme because epic space movies love epic scores. I also think it will clarify world perspective.

DISCLAIMER: I decided to use still photographs/art to create a narrative structure for all musical examples in this post. Keep in mind that I am not an editor! You’ll have to use your imagination to see the movie underneath the still images. Hell, you might imagine a way better use for the music, and if that’s the case please email me.

But in any event, it’s time for our first example. Okay, deep breath… here goes!

As a filmmaker, you must have experienced how big that sounded, right? That’s the point. I wasn’t going for subtlety. I was going for something really powerful. I wanted it to be loud, titillating, and I wanted to bring you along for a ride whether you liked it or not. I wanted you glued to the screen, inside that world, and I wanted to make it really hard to escape.

When the music achieves this over-the-top meltdown, it can enlarge the screen. That’s the aim. If you watched it all the way through, and if you were still in the narrative I presented when the video stopped, then that’s a success for world perspective.

The Disadvantages of World Perspective

I've been talking world perspective up, and rightly so. It's an essential type of film score. I particularly love this perspective for how thrilling it feels.

But if world perspective is so great, if all the Hollywood blockbusters are using it, every director should strive to absolutely use it everywhere, right?

Nah. Not even close.

World perspective does have some considerable disadvantages. When the scale is large, the tendency we composers have is to always go large with it. What about intimacy? What about the small moments? The details? The tendency is to stay big and never go tiny.

The film scores that consistently go large are in danger of glossing over the quietest moments, the nuances in a film. With a grand scale, it's so easy to just overdo it.

Further, if a composer prefers composing in a large world perspective, he probably won't feel as comfy composing for a movie that has a smaller audio perspective altogether. It's a danger, though we film composers are a hardy folk and love to be challenged to think outside of ourselves.

Speaking of which, there has to be a “smaller” sounding type of perspective, right?

Surely, there are audio perspectives that we composers can use that are more appropriate to capture the nuances of emotion, right?

Absolutely. Enter Relational Perspective.

Relational Perspective

I recently have been studying the movie The Sixth Sense. I think it is one of James Newton Howard's best scores. I also think it's a criminally underrated score. I felt that Howard managed to get into the minds of the two main characters beautifully because he captures nuances masterfully. [SPOILER ALERT] The relationship between a man who doesn't know he's dead, and a very troubled boy who can see ghosts, provided a rich relational context for Howard to work with.

To me, the strength of this score comes from the subtle push and pull of emotions we see between these two characters. When you listen to the score and watch the movie together, you'll notice that the relationship between Bruce Willis's character (the child psychologist) and Haley Joel Osment's character (the boy) is deeply rich and full of emotionally engaging moments. It’s sometimes perilous, sometimes, frightening, sometimes incredibly joyful. So many parts of the emotional spectrum are presented.

Though the audience doesn't know the dynamic of the relationship until the end of the movie, the boy knows the doctor is a ghost. These two characters are drawn together to solve not just the boy's problems but also to help Bruce Willis's character realize that it's time for him to move on. To me, because I'm a bit of a geek when it comes to how James Newton Howard composes film scores, he truly captures the dynamic of this relationship by zeroing in on this complicated relationship.

The Size and Scale of Relational Perspective

When you’re talking to someone who might make you feel a little uneasy, do you show it? No, of course not. But if there was a musical score to that moment, then the music would undoubtedly express that uneasiness for you.

Relational Perspective tends to have a small-scale and size because it can zero in on things that we feel as opposed to actions that we can see. This perspective is tiny when compared to the massive scale of world perspective because the object is emotion.

If relational perspective could speak, it might want to say:

This movie doesn't belong to the world that these characters belong in, but simply to the subtle push and pull of emotions that you can feel and barely perceive.

Relational perspective follows the emotion. We feel a tug of an emotion in this direction, we composers follow that emotion and see it through. We feel the gravity of emotion in a different direction, we composers follow it and see that through too. It’s all about emotion.

Relational Perspective in Practice

In practice, the relational perspective can work if it’s focused on the many emotions underneath a performance of an actor. If the actors are really connected, if they have that wonderful chemistry like James Stewart and Kim Novak did in Vertigo, than we are pulled into the emotions these two characters are feeling, fully and completely.

In working with the relational perspective, it’s my preference to lock into the actual actors’ performances. I enjoy seeing how two people interact, how there are natural beats of silence, how there are moments of heightened emotions. Chemistry is everything. I absolutely love reading the subtle body language of two very experienced actors in the throes of an amazing take. I love the subtleties.

To help illustrate relational perspective, I chose to do something a little different. I chose to illustrate a partnership between a puppy and cat, partially because it makes me happy but also because there’s a narrative in these images that I think lends itself to subtle emotions. Plus, it just makes me happy to look at the two animals interacting with each other:

Do you see how this example manages to capture some subtle emotions? How the emotion shifts?

As a director, it can make sense to use relational perspective throughout your film, especially if you have two extremely commanding performances from the lead actors that constantly push, pull, and tug at each other emotionally.

But, just the same as world perspective, there are disadvantages to defaulting to relational perspective. Sometimes, focusing purely on emotions means forgetting about some really important basic concepts in film scoring.

The Disadvantages of Relational Perspective

You might think that I'm a big fan of relational perspective judging by how much I look up to James Newton Howard. I look up to him because he's such a master of that perspective AND he can unify his score to be 100% cohesive. That, and he’s not afraid to go big and ballsy, like in the world perspective way. I'm looking forward to the lunch I'm going to have with him one day because I want to say how much I appreciate his work.

As I hinted at however, the danger with composing primarily with a relational perspective is that emotions can run wild and often pull a composer in many different directions. This can in turn lead her to create a score that is not unified. The composer is in too much temptation to create music that feels discombobulated, un-anchored, and has no sense of direction.

I also think relational perspective is one of the very hardest perspectives to master in film scoring because we're trying to catch not one, but thousands of butterflies in a small net. This gets really bad when we composers start to geek out about sample libraries, which offers us millions of patches to choose from… a special danger.*

And one of the biggest problems with relational perspective is that it can't often get it's head out of it's own ass and go big and crazy. When it's time to have the music go really large, composers under the relational perspective mindset might be too tempted to stay small. Why go large when the entire score so far has been about the small plays of emotion?

But anyways, relational perspective done well is incredibly powerful because it’s communicating an emotional perspective to the audience. The real question is whether or not this perspective is appropriate for your film. Sometimes your film might need this sort of intimate touch, and sometimes you might want to be more gruff and large. And if neither of these seem right to you, there are other options.

The next perspective I explore in this article is an interesting way to begin to capture both the scale of a world and the nuance of emotions but not be totally limited be either of them. I like to call it Character Perspective.

Character Perspective

It’s time to jog your memory: Think of the last film you watched where the lead actor was so commanding that you couldn’t help but see things from his or her point of view. You ended up seeing things from that one character’s eyes, to the exclusion of all others. You probably walked away from the movie still thinking about that character, how she should have done this, how he should have done that.

When one character is so strong, so potent, and so compelling that we end up feeling what this character feels, seeing what this character sees, and living vicariously through the performance, a score might be done really well if it takes that character’s point of view throughout the film.

If the character experiences something very large, we can feel it as the audience, and the music can feel as large as the world. If the character experiences something very small and subtle, the music can feel just as small as the tiniest emotions. Character perspective can go as large or as small as it needs to, as long as it describes a character’s experience well.

One of the best examples of character perspective, in my opinion, would be Room. Though Brie Larson got the accolades, it was the perspective of the boy Jack we got to see throughout the movie, played by Jacob Tremblay. If you watch closely, we see mostly what the boy sees throughout the film. We experience what the boy experiences too. We hear what the boy hears, too. Stephen Rennicks‘ score is a delightful listen too, easily capturing the boy’s perspective.

But does character perspective only work if there is one strong character? Well, there are other ways to apply character perspective in film scoring that can revolve around groups of characters, too.

The score for To Kill A Mockingbird is an excellent example of a film score taking the perspective of a group of characters. Elmer Bernstein's score for the movie is whimsical, delightful, and light. It's a fantastic juxtaposition to the subject matter. To give context, Elmer Bernstein couldn't find the right tone for the score until he wrote the music from the childrens' points of view. Isn't that interesting?

Another great example of character perspective that takes the perspective of a group, in my opinion, is the score for Sicario. You can agree with me or not, but it is my belief that the soundtrack, as large as it sounds, doesn't really take on a world perspective, nor does it take on a relational perspective, though both of those scales are present in that score. What if you listened to the score as if the music came from the perspective of the cartel?

The thundering drums, the orchestral crescendos and rips, the sound design and synths, the distortion on the drums... The music is slow; Dangerously teetering on the edge. To me, that movie is all about trying to control the uncontrollable, aka controlling the cartels in Mexico. The characters are all invested in seeing that come to fruition (though with radically different ethical standpoints). All the while, the supremely wild menace of the cartel is banging away in the background, threatening to tear everything apart.

Interesting slant on that score, right?

Character Perspective In Practice

What I find really interesting about character perspective is that you can choose to find really odd perspectives, sometimes just barely beyond the edge of consciousness.

For this example, I chose to illustrate an unconventional perspective in horror film genres. The idea: Sometimes the main antagonist isn’t all bad. He or she just seems bad, but there’s a little weird altruism hiding inside. It’s the actions of this character that are absolutely horrific, but the motivation isn’t all bad. One need not look further than Thanos in Avengers Infinity War and Endgame to see the merits of a slightly altruistic bad guy and how rich that can be for a narrative.

In the video below, you’ll see a series of images that are common to horror films. You’ll see a woman walking around, you’ll see some indistinct charcoal sketches, and you’ll see a color palette that is grimy and gloomy. You’ll probably assume that the woman is possessed, and you’ll probably assume that the music is trying to express the shock and horror of that possession.

I wanted to express that there was something more than just extreme evil going on. Extreme evil that is 100% malevolent in a movie is boring! Instead, this sketch was more about the so-called “demons” possessing the woman in the photos. What if they weren’t demons, but were lost souls looking for redemption by possessing a living woman?

With this perspective, I naturally had this thought: “Wow, they must be desperate to get out of wherever they are.” Then, the whole mini-movie came together. We have a flock of misunderstood souls clinging to a living human being, but they are so desperate to escape that they dragging her down with them.

To achieve this perspective, I took a simple piano piece that has it’s own strange tonality and I worked it to be incredibly unstable with the help of an orchestra. I wanted it to capture the perspective of the lost souls desperately wishing to escape their situation but doing it in a terrible way:

Picking a character perspective like this can work wonders for your movie. For you, as the filmmaker, do you see how this really strange point of view adds a level of subtlety that can challenge your audience to see something more? To perceive that there is more going on? Can you see how doing this can make your story stick out and stay with the audience a bit more?

The Disadvantages of Character Perspective

Writing from a character's or a group of characters' perspectives is a different way of looking at the typical film score. It's not the world that most important, it's how that character views that world. It's not the emotions in the film that matter nearly as much as that character's perception of the emotions.

Of course, there is a slight problem: What if the character cannot actually see the largeness of the world? What if the character cannot perceive the push and pull of emotions? What if a character is totally cut off from his or her emotions altogether, and there are important events happening in the emotional world that he or she can't see?

Since character perspective is so localized, anything not perceived is in danger of being discarded. I'm certainly not suggesting that a movie has to STAY in a character perspective the entire time. Sticking to just one character's perspective throughout a movie has to make sense. It does for Room, though there are quiet moments outside of the boy’s experience that we get to experience as well.

The MELANCHOLIC Disadvantage to World, Relational, and Character Perspectives

World, relational, and character perspectives are all very serious ways of approaching a film score.

The world perspective is so big and large, crushing in it's perspective that it can easily be overwhelming and overstimulating. The relational perspective is smaller and more intimate, a bit like a narrator in a regular story, but can easily lack focus and direction. The character perspective can be large or small, depending upon the worldview of the character or group of characters that we are to get the viewpoint of, but only of that character.

All three perspectives tend to have a possibility for a repetitious monotony of seriousness, and sometimes we just don't want to be so damned serious. Sometimes, we just want to have some fun!

So, why can’t we?

Why can't we laugh and be silly? Why can't it just be light and airy once in awhile?

I'm afraid that without a little levity, all the movies out there would be a ridiculous bore. And it’s the levity which Juxtaposition brings that can shake up the vibe in a lovely way.

Juxtaposed Perspective

Did you ever watch You Can't Do That On Television on Nickelodeon when you were younger? There was a point in every show where they'd have the opposite sketches; All the characters did everything backwards.

People who loved hamburgers all of a sudden hated hamburgers. A very frugal family instantly became spendthrifts. A girl who wanted nothing to do with a boy begins fawning over him. All of the characters knew this would happen on every show, too. "Oh... I get it. It's the introduction to the opposite sketches." (this was also the show where if you said "I don't know" out loud, you would get slimed. It’s a fun YouTube rabbit hole).

Juxtaposed perspective is like the opposite sketches: Find a song that makes a scene feel radically different than what's happening in it. In doing this, you would be taking an approach that is from the perspective of humor and irony. There is a rich history of juxtaposition to exemplify this wonderful tool for film music.

Take the first scene of Watchmen (2008). In this scene, we see the Comedian fighting a masked mystery man in his high-rise apartment. This fight scene is brutal! But it’s the fact that Nat King Cole's Unforgettable is playing in the background, a slow moving and deeply emotional tune, that the scene feels light. It’s even… comical. The scene culminates with the Comedian falling out of a high-rise window in slow motion, while the song slowly comes to an end after he hits the ground and dies.

There are a couple more examples of juxtaposition that I think are worth noting. There's Michael Madsen's character in Reservoir Dogs cutting off the ear of a captured police officer to Stuck In The Middle With You. Then, there's Uma Thurman's character preparing for a battle in a Tokyo nightclub under the sway of the 5 6 7 8's lovely song Woohoo-oo-oo-oo.

For the most part, juxtaposition has been achieved through licensing music to be synced to picture. What is intoxicating though is that composers haven’t had the chance to adequately explore juxtaposition directly. What I mean is that composers aren’t often asked to create cues that are inherently juxtaposed and opposite to the action of the cue. Instead, directors pay lots of money to use music that was already commercially released, but there's no reason why composers couldn't actually compose juxtaposed music to help deliver some levity.

Juxtaposed Perspective in Practice

Now onto the fun part! For this example, I decided to do something really silly. After all, I love to embarrass the people around me by singing in an operatic voice. Why not use it?

Juxtaposition brings levity, and opera can be very, very comical:

I could have scored this mini-movie a lot differently, of course. I could have tuned into the emotions of the characters. I could have taken a perspective of the office looking in shock and horror at this fight. But really, what’s the point of that when we could just make it really funny?

By using juxtaposition, this entire scene becomes lighter and enjoyable. Funny! The use of juxtaposition is a great way to keep things light, but like all the perspectives I’ve discussed here, juxtaposition has it’s disadvantages.

The Disadvantages of Juxtaposition

The following quote from Rainer Maria Rilke in his Letters To A Young Poet is an excellent way to introduce one of the main disadvantages with juxtaposition:

Today I would like to tell you just two more things: Irony: Don’t let yourself be controlled by it, especially during uncreative moments. When you are fully creative, try to use it, as one more way to take hold of life. Used purely, it too is pure, and one needn’t be ashamed of it; but if you feel yourself becoming too familiar with it, if you are afraid of this growing familiarity, then turn to great and serious objects, in front of which it becomes small and helpless.

As you might have guessed, juxtaposition can be ironic, and that irony can be overused.

Another way to put it: Choose your moments to use juxtaposition, or else you'll lose the element of surprise.

There's another issue too. I think there is a dark side to using too much juxtaposition. Have you ever met an incredibly sarcastic person? Of course you have. They are everywhere!

If you're anything like me, you'll wonder why this person spends so much of his or her time masking how they really feel under a witty, sarcastic result.

Sarcasm, to me, hides what's truly beneath the surface. And further, it's not unreasonable to think that sarcasm is a gateway drug to cynicism. You might disagree with me entirely, but I've seen sarcastic people turn incredibly cynical later in their lives. And cynicism in general? Whoa... I'd rather not be around that energy if I can help it, thank you very much!

This is the danger of using too much juxtaposition: You might unwittingly present cynicism to the audience. If that's what you're going for, then do it by all means. But cynicism is incredibly exhausting.

I think a good guideline to keep in mind is that juxtaposition done with tact and timing is intensely powerful. But when it's relied upon as a staple, it's a little overbearing.

Use it with caution, not abandonment!

I've been focused heavily on narrative film scoring perspectives throughout this post so far, and how fair is that? There are so many hard-working documentary composers out there and I wish to tip my hat to them. Therefore, I only wish to share just one final type of audio perspective (though there are many others), and it's one I often hear in documentaries: Idea perspective.

Idea Perspective

Though it's not what I enjoy playing anymore, I certainly appreciate and love listening to jazz. To me, jazz is like an interlocking and evolving web of ideas. One idea bubbles to the surface. This first idea it inspires new ideas from others in the group, which of course inspire more new ideas. Jazz done well is a ton of ideas being built upon.

When I think of ideas in the real world, I also think of the evolution of scientific inquiry. Though I will admit that I definitely don't have an expert view, what seems to make scientific inquiry so powerful is that scientists are always questioning what ideas were presented before in the quest for an ever-expanding truth. The ideas of the past inspire the ideas of the present and future. There always seems to be a new paradigm that disproves an older theory. A decent example of this is how quantum physics shook up the paradigm of Newtonian physics.**

Idea perspective is when one idea leads to another, which leads to another, and leads to another, and so on. It's really fun to dig into as a composer!

Idea perspective has an unmistakable vibe of wonder, awe, and a feeling of brightness that serves documentaries well.

Speaking of which, there are some really great examples of this perspective in action. One of my favorite documentaries, just because I'm a big appreciator of typography,*** is the movie Helvetica by Gary Hustwit.

Helvetica is all about the history and impact of a font (or to be more accurate, a typeface) and how it's introduction changed the look of our modern cities as well as graphic design, forever.

Based on our discussion so far, you might be tempted to wonder if the music represents the actual typeface of Helvetica, but I really don’t think it does at all. The music on the soundtrack tends to bring us on a journey of an idea from it's beginnings in 1957 to ubiquity in advertising and street signs in American cities in the present time. The music represents the rich history and impact of Helvetica, how one thing led to another, how one idea for the use of Helvetica sparked a revolution in advertising and graphic design.

Idea perspective has an unmistakable educational vibe that seeks to inform us of how ideas evolve. It's full of wonder, of awe and learning. Idea perspective is just about perfect for documentaries. It just works.

Idea Perspective In Practice

In the following video, I strung together a bunch of photos that showed us the design and then the construction of a building. I composed in a way that weaved together a bunch of small inspiring ideas, ones that create a structure. I wanted the music to weave ideas upon each other, to move the story forward:

The Disadvantages of using Idea Perspective

Ideas have a natural way of building upon themselves. When we’re in our element and the ideas are flowing, there is an unmistakable vibe of growth. But it’s strength in expressing growth is also it’s weakness. Sometimes we don’t want to express the perspective of growth. Sometimes we want to express death. Sometimes, we don’t want the audience to feel that air of awe and magic.

Further, while idea perspective lends itself so naturally for documentary features, it might not be the most appropriate for slower moving dramas that really don’t need a lot of movement.

I like to cite Moonlight as having a perfectly paced score. Can you imagine if you took the music of Octopus Project and played it while watching Moonlight? I suspect it would feel terrible! Octopus Project’s music has such a light, bright, zooming sound to them that it seems almost cruel to think of watching Moonlight at the same time. It works so much better with the slow moving score that it has.

This leads me to the main issue, the main reason why it’s a good thing to look at so many different audio perspectives.

The perspective you choose must be appropriate for the film you’ve created.

If you decide not to think about what type of perspective is appropriate for your film, you are missing one of the most powerful ways to communicate your perspective and have the most effect on the audience. Further, if you’re interested in growing your career and experiencing more success, it’s my strong belief that you are shooting yourself in the foot by ignoring it.

Let’s not do that, okay? Let’s now talk about how to get your movie paired with the most appropriate perspective, one that will definitely make your story more vibrant.

Determining The Right Perspective For Your Film

It’s silly to assume that a one-size-fits-all treatment is going to work for each and every story you ever put together.

Creative movies need creative scores that match the perspective that the director wishes to communicate to the audience, and sometimes that requires thinking outside of the box. Sometimes it requires breaking all of the rules.

Further, the composer has a big responsibility to make the movie incredibly enjoyable. It’s all too easy to use the wrong audio perspective and pull the audience through a movie with a meat hook through their jaws. Even Quentin Tarantino doesn't often use composers, stating “I just don’t like the idea of giving that much power to anybody on one of my movies.” (Milian, 2009).

To help us do better work, I think considering different audio perspectives can help us all tell a better story.

If you just want a score that sounds like [insert famous film composer here], I beg you to consider that a different approach (and perspective) could be more appropriate. If you can get a more appropriate film score, than your film has more power to communicate it’s perspective!

The issue of scale, of vastness, is also really important when you're nailing down how you want the score for your movie to feel. When you watch a movie like Room and blast the soundtrack of Blade Runner 2049 in the background, can you see exactly how uncreative and excruciating and inappropriate that is?

If budget isn't a concern for you, you don't necessarily need to go world-perspective big with huge orchestras or incredibly large synth soundscapes. You could start by asking, "what is the size of my story?" Or, "Who does my story belong to?" I would highly recommend that you answer these questions before you even reach out to a composer. Doing so can give you a sense of mastery over the process of choosing the correct person for the job. After all, many composers can become well-known for a particular audio perspective.

Alas, there are so many composers out there, right? How do you choose the right one?

Finding the Right Composer for the Story

If you met a composer randomly, you must keep in mind that just because you get along with her doesn't mean she’s the right woman for the job. You must keep in mind that just because he’s relatable doesn’t mean he’s the right man for the job. You have to get to know what makes a composer tick. To help you with this, I recommend that you interrogate composers!

Here's some questions I would ask if I were interviewing composers:

"How much experimentation have you had with a very large-sounding orchestral score?"

"When you want to express something musically that's really small, what do you do? What is your process?"

"What sorts of things do you do when you want to get in deep with what a group of characters are feeling?"

“How do you work to unify a film score when there is so much happening inside a story?”

"When you approach a documentary, what anchors you in your approach?"

If you've made a choice and you're starting to work with a composer for your film, discussing audio perspective is a solid move to make, even before the spotting session begins. I am convinced that it's important to take the time to explore the film, talk about the film, and get in touch with the film before you set the composer loose on it. Basically, you’ll prime the composer to deliver a unified score that digs as deep as the story that you wrote.

Beyond that, you’ll have a better chance to delivering a perspective to the audience that has the opportunity to change them, that will stay with them.

You have a chance to help them expand their horizons.

Communicating Your Film’s Perspective With Music

Choosing the right audio perspective matters. Vital. When you choose correctly, your film becomes more powerful because the perspective you are trying to share with the audience is that much more compelling.

If we want to communicate the overall vastness of the universe, we have to come from the universe's perspective. If we want to get up close and personal, we need a smaller and more intimate perspective. If we want to express a character’s perspective, the music really needs to come from that character. And sometimes if we want a humorous perspective, a little juxtaposition could be just the ticket.

You can transport the audience inside the perspective that owns the story. Like Chiron in Moonlight, like the cartel in Sicario, like the world in Blade Runner 2049, like the children in To Kill A Mockingbird, you can bring the audience right inside the movie, to feel it deeply, to understand it, and to be enlarged by the experience.

This is why it’s so important to match the audio perspectives in a film score to the perspectives in the story. That’s why music is so important. That’s why it shouldn’t be an afterthought, an addition to an already stretched-thin budget.

Music is the best way to change and expand the audience by effortlessly and non-invasively delivering a fresh perspective.

And I really mean it: If we can take charge of the stewardship of communicating a new and fresh perspective to the audience, if we deliver it with care and careful consideration, we have the opportunity to improve people’s lives.

We can offer the shock that someone in the audience needs to become a better person altogether. Why can’t we do that? We aren’t necessarily saving lives like a doctor, but why can’t we have just as much effect on the world around us by helping people see that there is a world beyond what their eyes can see? Why can’t we help people be expanded in their lives?

The right music is a steward of the audience's experience of a film. It is a way to deliver an extremely compelling perspective. When the score is done appropriately for the perspective that the story wishes to communicate, it has so much power to expand the horizons of the people watching the film. It doesn't matter if it's world big or character small. It doesn’t matter if the perspective is as big as the universe or as small as a butterfly.

It also doesn’t matter if you spent $1,000,000 on the score or nothing at all.

What matters is that the music adequately expresses the size, scale, and perspective of whomever owns the story. When it does that, you can count on that movie having incredible power and much more success.

And that is my wish for you.

Please, leave me a comment!

Or, feel free to reach out to me.

More Articles on Film and Music

Footnotes

* I literally got a headache after writing this sentence.

**If you're interested in a really interesting scientific explainer video, check out the Double Slit experiment. This blew my mind.

***This entire website is set in Adobe Jenson Pro, a renaissance type that was made by Nicolas Jenson, a man so in demand that he kept 12 printing presses running at the same time. Aside from being a beautiful typeface, I love the history of it and the fact that it's been around since the 1400's. Robert Slimbach did a great job with the revamping of it.

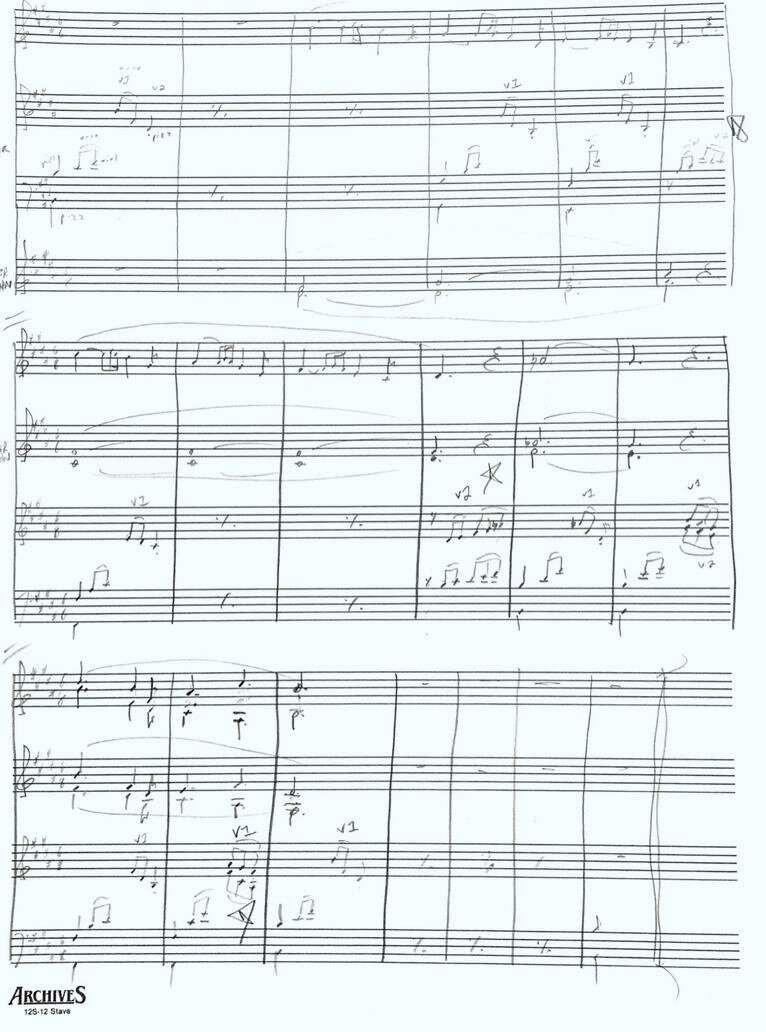

Facsimile Scores

Copyright Notices

All music that appears on this article was composed by Dave Wirth, Copyright and Published 2019 Fire, Fire, Red Star Down! ASCAP. All Rights Reserved.

So grateful to find this story:

Toronto-based pianist Richard Herriott got out of his flat just before it was completely engulfed in flames. Though he was lucky to escape with his life, everything in his apartment, including irreplaceable manuscripts of musical compositions, was destroyed.

Newly homeless and in shock, the entire community of musicians and music lovers rallied around him, and raised over $15,000 to get him back on his feet.

Richard Herriott:

"I just feel so fortunate that I can still be here to sort of appreciate it," he said.

"That's what's getting me through everything."

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-s-music-community-rallies-to-support-beloved-pianist-after-fire-destroys-his-home-1.5370525

About two months ago, my friend WT from AMBO Art and I went to a flea market in Texas. While there, we ended up finding this little gem, a Little Wonder Microphone:

The microphone didn’t work. The wires were from the original kit, and this little beast was assembled circa 1935. The wires almost fell apart in our hands, but we thought, “Let’s open it up and see what we can do with it. It’s already broken anyways”

The first day, we opened up the bottom of the mic, and began to open up the capsule. We didn’t make it too far:

The capsule needed a different tool to crack it open, though we did try this:

I thought, “Oh well. It’ll make a nice paper weight.” Two months later I brought the mic back simply to see if anything could be done, and that’s when it all came together.

The Dremel and a drill press took care of the rivets holding the capsule in place:

What we found inside was a cause for wonder because the transducer was a cylindrical piece of wood with a metal plate:

Since we had the capsule off entirely, and also since we just wanted to make this dead simple, it was decided to add a Piezo pickup in the capsule where the old transducer was, load up a quarter inch jack, and put it all back together again. This would make it usable without any extra equipment.

So, how does it sound? Pretty awesome on a guitar alone:

Then I thought, “What would it sound like in a mix?” Here it is on an electric guitar (left) and a piano (right):

Very happy with this new microphone! Gonna have to get my friend another round of cigars for his help…

All music composed by Dave Wirth, Copyright and Published 2019 Fire, Fire, Red Star Down! ASCAP. All Rights Reserved.

The music on your film is a powerful tool to deliver fresh perspectives, and believe me: Fresh perspectives are vital. This article goes deep into Audio Perspective, i.e. the music being written from the most compelling perspective in the story. Mastering audio perspective can make your movies far more relevant, relatable, and successful.

If you’ve ever wondered how you can use music to communicate a compelling perspective, this article is for you. Let’s hit it!